There are only a handful of players who one could say changed the fabric of the game. Jackie Robinson might be the most obvious example, breaking the color barrier and allowing blacks to play in the major leagues. On the field, Babe Ruth ushered in the live-ball era, and St. Louis Cardinals great Bob Gibson was a pivotal reason for the mound being lowered. These three players are in the Hall of Fame. Curt Flood should be among them.

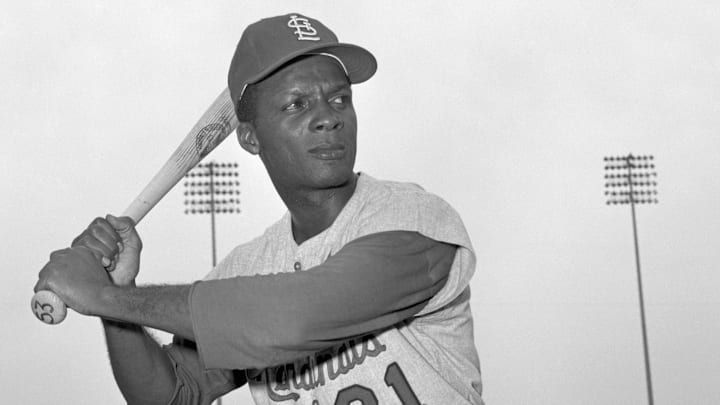

When it comes to the issue of players' rights to be treated as people and not as property, there was no bigger pioneer than Flood. A Cardinals outfielder from 1958 to 1969, Flood was known as a standout defender and won seven consecutive Gold Glove Awards while batting .293. But when the Cardinals traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies on Oct. 7, 1969, Flood balked.

Flood refused to suit up for the Phillies and took his beliefs to court, declaring baseball's reserve clause akin to slavery. The reserve clause, instituted in 1879, required that a player remain with his original team unless he were released or traded, giving players virtually zero control over their contracts.

Flood ultimately lost his case, which made it to the Supreme Court in 1972, and his reputation around baseball lay in tatters. According to Gibson, his teammate, Flood received "four or five death threats a day." He sat out the 1970 season, and his career was effectively over, as he played only 13 games in 1971 after the Phillies traded him to the Washington Senators, after which he hung up his cleats.

Flood gave up a part of his career to campaign for the rights of players around baseball, and in a classic case of losing the battle but winning the war, the push for free agency grew, and baseball struck down the reserve clause in 1975, giving players the ability to exercise free agency and have much more control over where they could play.

Flood died in 1997 at the young age of 59, and despite his immense contribution to the evolution of baseball, the Hall of Fame has never come calling. Flood's children have fought for his induction and for making his legacy more appreciated throughout sports.

Although any Hall of Fame induction for Flood would be more on the merits of his actions off the field than on it, there is still a case to be made for Flood making it in via his performance on the diamond. Flood's bWAR of 41.9 trumps that of several players in the Hall of Fame, including George Kell and Bill Mazeroski.

As appreciation for Flood's exploits and the sacrifices he made to achieve them, the Cardinals and Major League Baseball should commemorate Flood with a Hall of Fame plaque at the very least. If the Cardinals want to go further than that, a retirement of his jersey number of 21 would undoubtedly shine some much-deserved light on Flood and everything he fought for.